Lue tämä suomeksi

Students and graduates in the game industry have trouble finding work — true or false? More than a hundred students and alumni across Finland responded to a survey on the challenges and other experiences with finding an internship or employment. The questionnaire is a follow-up to interviews conducted with game industry professionals, the results of which you can read here.

Abstract

In January, 2019 more than a hundred students and alumni with planned or existing careers in game development responded to a digital survey. They were asked about their experiences with internships, founding companies, and the struggle of securing employment in the industry.

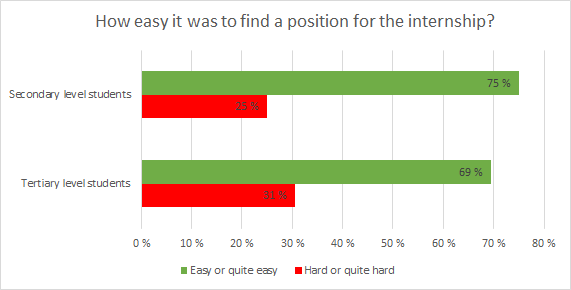

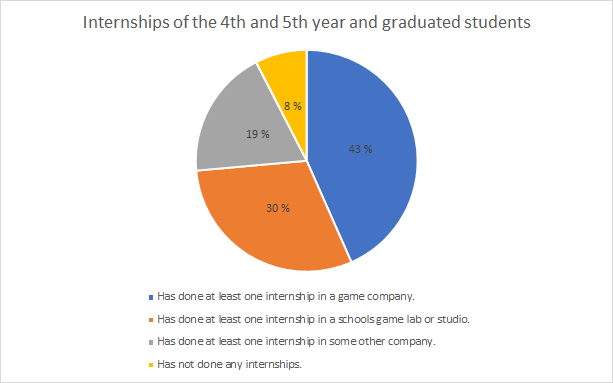

The survey’s hypothesis was that game industry students have difficulties finding internships and jobs. The results partly demonstrated and partly refuted this hypothesis. Many who worked as interns said that they quite easily found the companies that took them on. On the other hand, about one fifth (19 percent) interned at least once at their school’s own studio. The data on the level of difficulty in finding employment gathered from current game development students was unclear, as nearly half of those respondents (45 percent) had not yet sought employment in the game industry. Respondents were asked about their impressions on the availability of or access to junior game company positions. Eighty-seven percent of respondents said they considered securing entry-level positions in their industry to be difficult or quite difficult.

Respondents’ backgrounds and studies

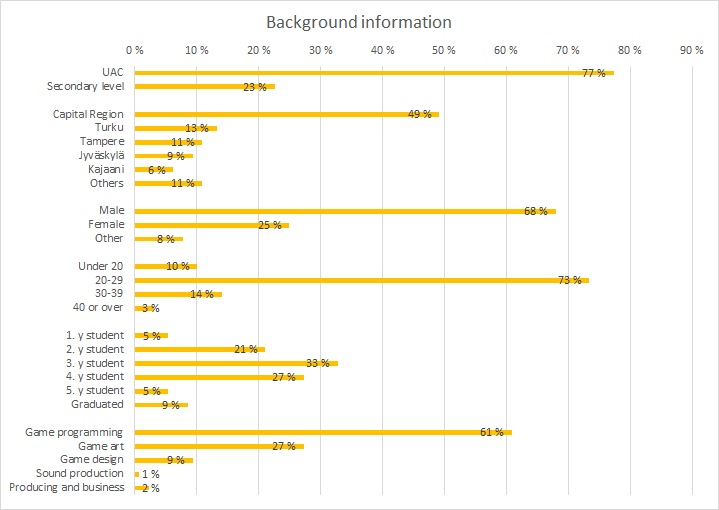

A total of 129 people responded to the survey during January 2019. A majority of the respondents, 118 people (91 percent) were students at the time and 11 people (9 percent) had graduated in 2017 or after. Respondents were enrolled in institutes of secondary education (23 percent) or universities of applied sciences (77 percent) across Finland; the most represented regions were Turku, Kajaani, Jyväskylä, Tampere, and the capital region.

A typical respondent was a young man from the Helsinki area with a major in game programming in a polytechnic institution (aged 20-29 = 73 percent, men = 68 percent).

Respondents’ employment situation and entrepreneurship

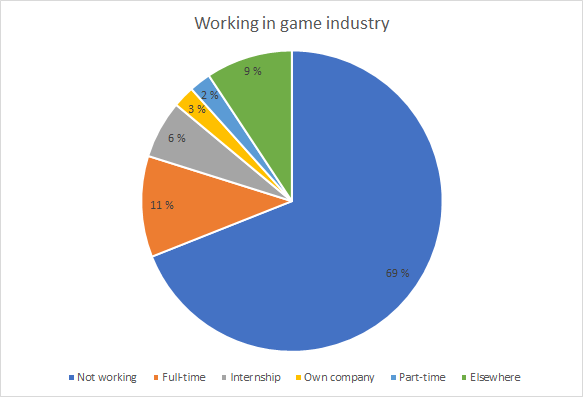

The survey asked whether the respondents were currently employed in a position matching their education. The clear majority, 89 respondents, said they were not employed in their own field. Three respondents said they were employed part-time, and 14 people said they were working as full-time salaried employees. Three others said they work full-time in a company they own or in which they are shareholders. Eight respondents said they were currently in a trainee programme, while 12 said they were in other circumstances; employed in a different field, working as freelancers, working in programming — but not in the games industry, which is visualized separately below.

The respondents were also asked about starting a game company of their own, for those who had already established one or were planning to. Six respondents had started a company, either on their own or with business partners. Forty of the respondents said they were planning to start a game company. Respondents said they found their motivation to go into business in their desire to become entrepreneurs (26 responses) and through finding good business partners (16 responses). Fifteen people said, however, that difficulty finding work as an employee was what drove them to try their hands at entrepreneurship. Other motivations were mentioned, such as the desire to work alone or be one’s own boss, the ability to make games of a very particular style, but also the option to get one’s game onto the Steam platform (which requires a company).

Internship

Most of the students surveyed are required by their schools to complete either one or two professional internships. These are usually completed toward the end of the degree curriculum, when students have managed to get some know-how and experience under their belts.

Well more than half of the respondents (76 people) had completed their first internship at least, while 53 respondents had yet to begin their trainee period. The questions that followed concerning the difficulty of finding an internship, for instance, were only directed at those respondents who had already undergone at least one internship period.

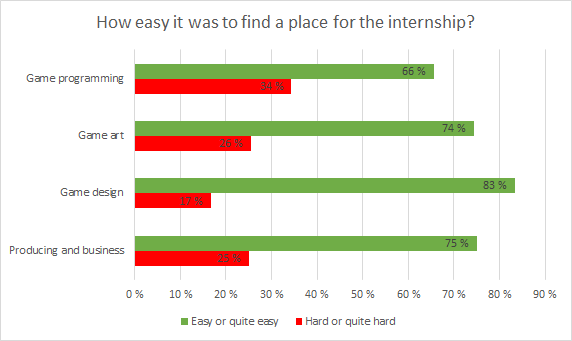

Respondents generally found their first internship to have been easy to find; usually, the position was found with help from the school. Personal contacts and networking also helped, as did various websites, such as the Neogames homepage. Students were placed in their school’s own studios, but some also found spots in companies outside of the institution’s influence. The first internship period typically lasted some 2-3 months. The difficulty of finding an internship can also be interpreted based on the specific fields within the game industry: students of game design felt they had an easier time finding internships than programming students. On the other hand, there were discrepancies between the number of respondents from each specific major, so the results should be interpreted critically (see diagrams 3 and 4).

The survey asked whether the companies at which students had interned were game industry companies or not, but many answered by providing the name of their school’s own game studio. In all, 14 respondents had interned at their school’s studio. This information was prompted by a question asking the students to specify the name of the company in question. Some of the respondents counted this as a game industry company, others did not. We ended up adding a third category, which finally were “game industry company”, “non-game industry company”, and “the school’s own studio”.

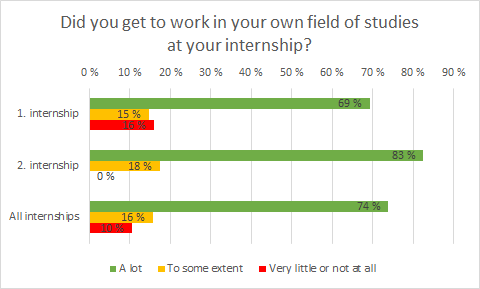

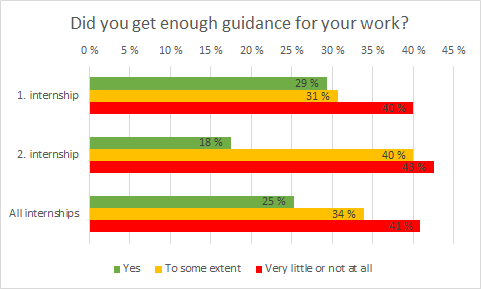

We noticed small differences between the first and second internships (see diagram 6). A clear majority of respondents were able to perform tasks related to their industry of choice at their internships, but those who were in the middle of their second internship reported getting even more relevant work. Sixteen percent of first-time trainees said they had been given very little or no industry-relevant tasks to perform, whereas no one in the second internship programme reported such a lack. First-time interns were offered slightly more guidance; it is nonetheless alarming that almost half of both groups of respondents said they received far too little training (very little or none) (see diagram 7).

Benefits of internships

Respondents were divided in their answers to questions about the benefits of internships. They were asked to assess the usefulness of their internships in terms of their personal development as well as employment, the aforementioned of which was considered more beneficial. Fifty-nine percent said they learned a lot through interning, and about 34 percent said they benefited from it somewhat. The differences in percentages between the first and second internships were negligible. The benefits of interning were seen to be meager; 30 percent of respondents said they benefited a lot, 36 percent somewhat, and 20 percent a little or not at all. We noted some differences here, as 27 percent assessed there to have been a lot of benefits after the first internship, up to 36 percent for the second.

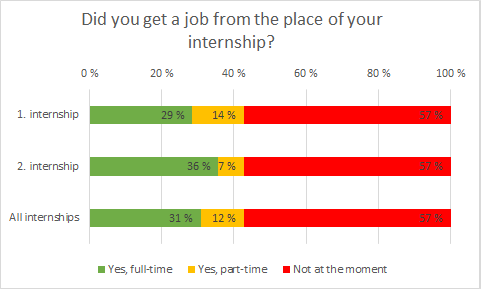

A 2018 round of interviews with game industry professionals found that, ideally, internships should lead to employment. This is far from the truth when asking students: more than half of student respondents were not offered jobs after the end of their internship period. The likelihood of being employed full-time rose with the second internship; about one third in the survey said companies offered them a full contract after their second internship. First-time interns were offered more part-time or freelance work. This split seems logical, considering the amount of time left in students’ degree studies is shorter for those in their second trainee program (see diagram 8).

Second internship

The survey asked respondents about their second internships, should they already have started or completed it. Forty of the respondents had completed their second internship period; they said they found finding the second internship easier than the first. Some interned for a second time in the same company or institution. Those who faced difficulties said it was partly because they wanted to find an internship at a game company following the first internship at their own school. The second internship typically lasted as long as the first one, 2-3 months.

Job applications

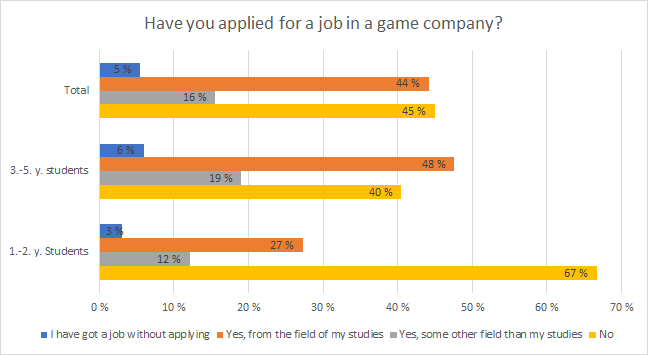

The survey found that 77 respondents had applied for work in-game companies; the applications of 57 people were for positions in their field, while 20 said they applied for work that did not match their education. Fifty-eight respondents had not yet applied for work at all. A small number (seven people) said they had been employed without applying for any positions. As expected, job applications increase with the number of years a person has studied; about half of students studying for 3-5 years had applied for work in their field, while only a little over a fourth of students in their first or second year had actively sought employment (see diagram 9).

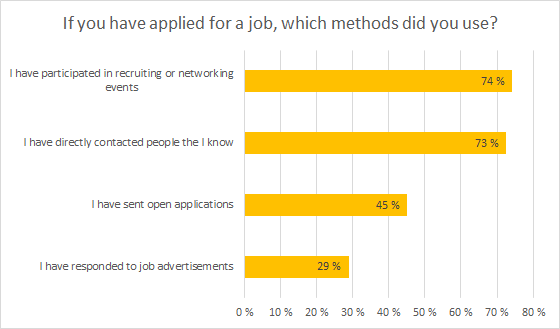

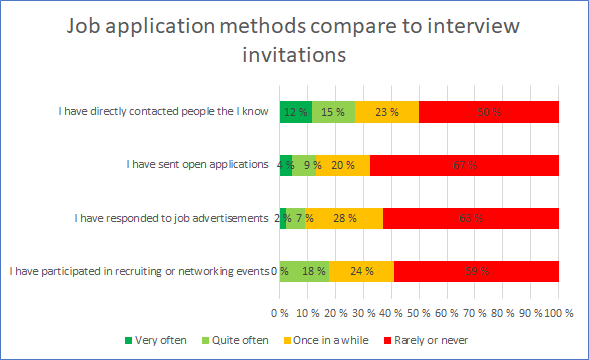

Respondents said they sought work in quite traditional ways (see diagram 10): about three quarters of them said they replied to job ads or sent open applications. Just under half said they directly contacted acquaintances in game industry firms, and a smaller proportion said they had attended recruitment or networking events. Some other forms of employment were mentioned, such as the possibility of staying on with a company after the third internship.

Almost two thirds of respondents (75 people) said they sent less than six applications for game-related positions. Eighteen people said they sent 6-15 applications, and 10 people sent 16 applications or more. Two thirds said they were very seldom or never invited to an interview or other job-related meeting. Fifteen respondents said they received occasional calls for interviews, and 12 said they had been invited often or very often.

A small number of respondents (27 people) applied to work outside of the game industry, and 15 people said they had found employment outside of their field. These included positions in retail, IT support, the food industry, and event management. A few respondents said they were working in game-adjacent jobs, but not in game development proper. Respondents had negative attitudes toward finding junior-level work in the industry; 87 percent said they considered finding work difficult or quite difficult.

Strengths and weaknesses in job applications

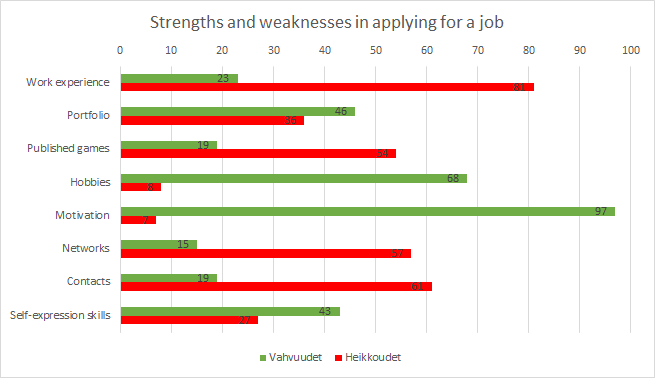

Respondents were also asked to assess their own job-hunting strengths and weaknesses. They were allowed to tick as many of the options as they wanted and were given the opportunity to describe their feelings in their own words. The most popular response was “motivation”, which 97 percent of respondents mentioned as a strength. The second-most popular strength cited was “recreational enthusiasm”, and just under half of the respondents said skills in portfolio managing and self-expression were paramount. Those respondents who had already secured employment said that luck, a positive reputation, previous studies, and innovation all helped them find work.

The greatest weakness reported was in prior work experience, which 81 percent of respondents said slowed down their job-hunting. A little over half said that contacts, networks, and published games were all weak points. Other things mentioned as weaknesses included worrying about social interaction, lack of confidence, learning disabilities, and a lack of energy in filling out dozens of applications.

Cross-tabulation

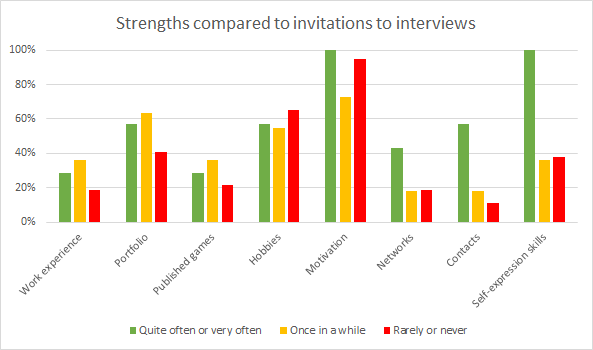

Analyzing the correlations between strengths and weaknesses in terms of the number of job interviews yields interesting results (see diagram 12). Roughly speaking, certain traits and backgrounds can either help or hinder access to job interviews.

Often or quite often people were called in for interviews who had assessed their self-expression to be a strength. Although the responses do not show a direct link between high confidence and the respondents’ abilities to sell their know-how, we can construe a correlation. Game industry professionals rated communication skills very high on their list of positive qualities, so perhaps this can also help explain the confluence of these two skills.

Strong contacts and networks were also helpful in getting job interviews. Motivation, which almost everyone considered a strength, was shown to have little effect on the likelihood of getting an interview. Motivated job seekers said they received invitations “quite often or very often” as well as “seldom or never”. Having a recreational interest was rated second in strengths, but did not correlate with positive responses to the frequency of job interviews.

The self-assessment of personal weaknesses in job hunting brought nothing new to the results as such, but rather inversely follows the strength trends.

Strong contacts and networks were affirmed to correlate with a higher frequency of job interview invitations (see diagram 13). Half of the respondents who had contacted industry acquaintances directly were very often, quite often, or occasionally met with interview invitations. Direct contact was percentually the strongest contender compared with other methods of job seeking. Sending out open applications was found to get the worst results.

People who received job interview invitations were united in that they were late-stage students, they had finished their internship(s) mainly in game companies, and they had self-assessed self-expression and portfolio skills as strengths.

When game industry professionals were interviewed about the qualities that were most prized, they mentioned published games, recreational passion, teamwork and communication skills, motivation, learning ability, portfolios, and basic professional know-how. Not all of these were options in the section on strengths in the student survey, but coinciding options produced results that both backed up and differed from the qualities brought up by professionals.

Those respondents who mentioned their portfolios and published games as their strengths received many interview invitations, but recreational enthusiasm and motivation did not ensure a meeting. It may also be that professionals and students understand the terminology differently. The survey’s “self-expression” option can be seen to equate with “communication skills”; this quality saw the most correlation in the high number of interviews. However, the professionals did not mention networks or solid contacts as aids to employment. Established companies do not necessarily observe the need or lack of such contacts in the same way as applicants do.

Only 14 respondents said they were employed full time in jobs related to their field of study. It is noteworthy that nine of them had completed their internships in game companies. These lucky few were also employed by the companies they interned at. As the number of these successes was so meager, the results cannot be used to deduce general conclusions.

Highlights from the data

About one third of respondents said they planned to start a company or had already done so.

Respondents’ first internship tended to be found through their school, either in the institution’s own game studio or in an outside firm.

Trainees had the opportunity to work on many tasks relevant to their own specialization during their internships, but many reported shortcomings in the quality of guidance offered.

Respondents considered their internships meaningful and useful for their personal development, but not for finding a job.

Networks and contacts are important in job hunting: those respondents who had directly contacted acquaintances in the industry received the most invitations to job interviews. Most of the students used more traditional means, namely open applications and responses to job ads, but they did not lead to employment as frequently.

Those who mentioned networks and contacts as their strengths also received more interview invitations, as did those respondents who listed self-expression as a strength. Motivation and “recreational enthusiasm” did not appear to correlate with a rise in interview invitations. This should not, however, be used to deduce the conclusion that high motivation or recreational passion are negative traits in job hunting.

Attachment: Survey of internship and job search (Google Drive)